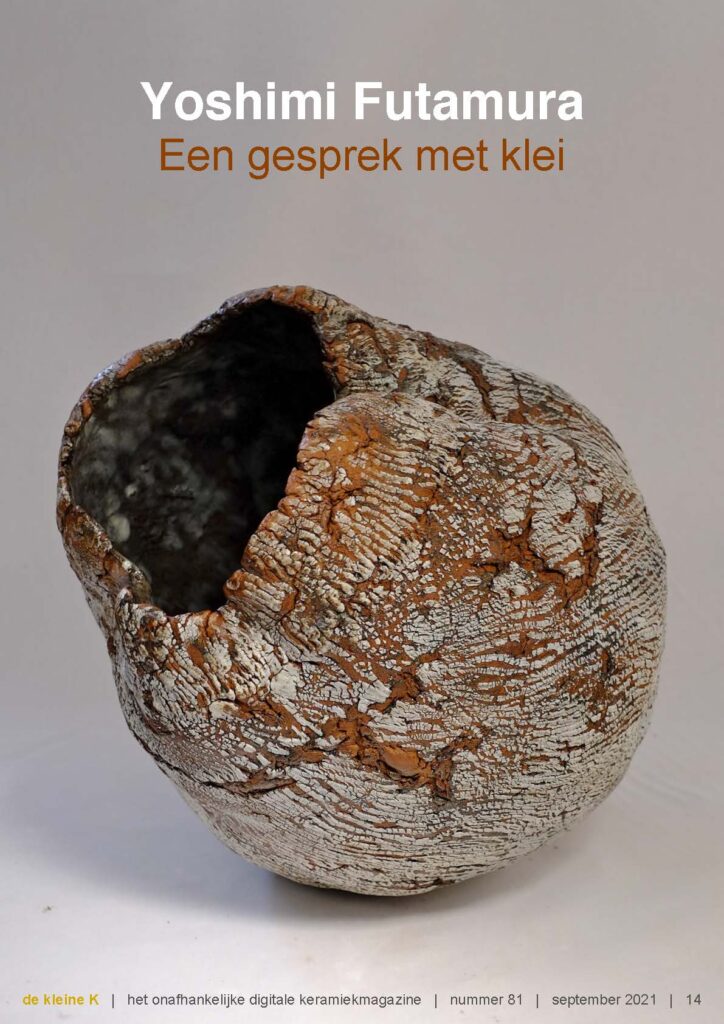

A conversation with clay

De Klein K

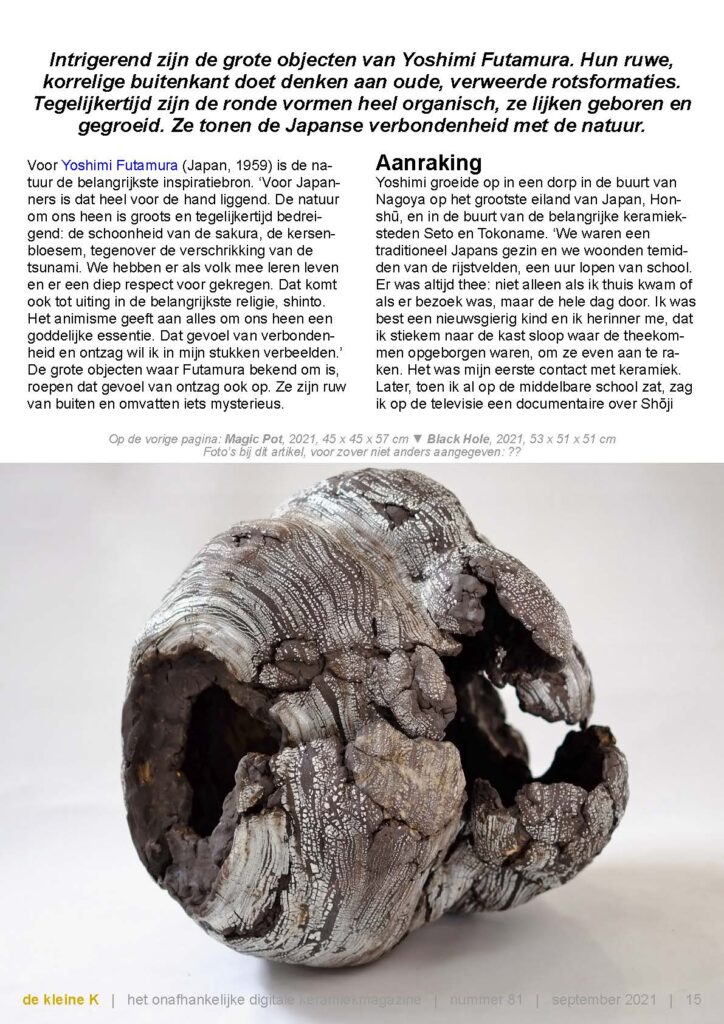

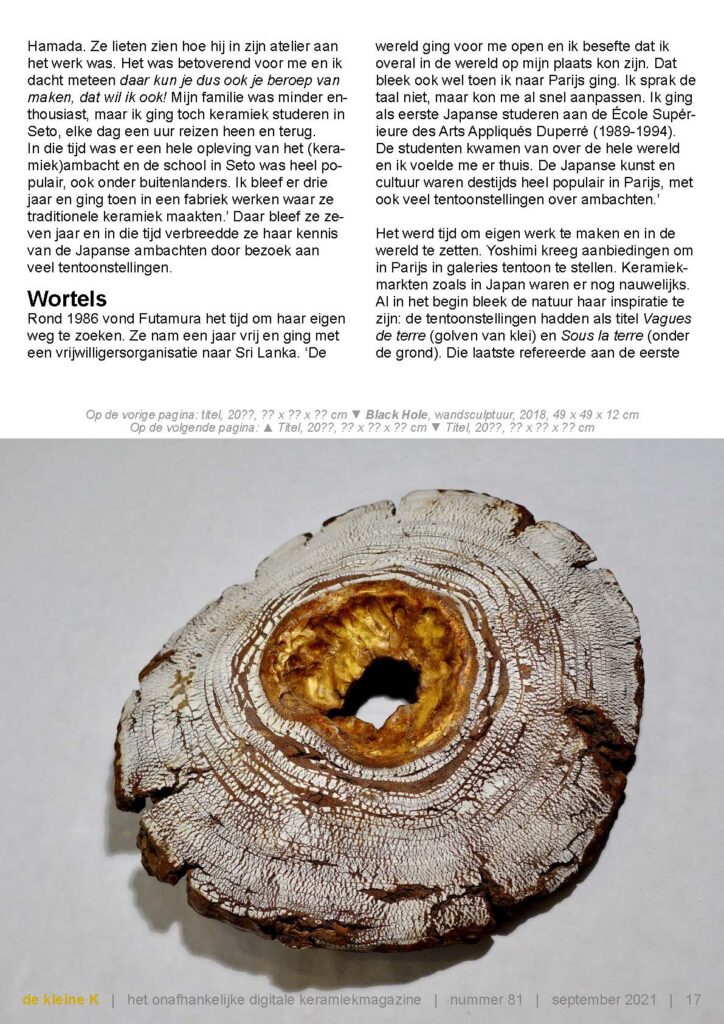

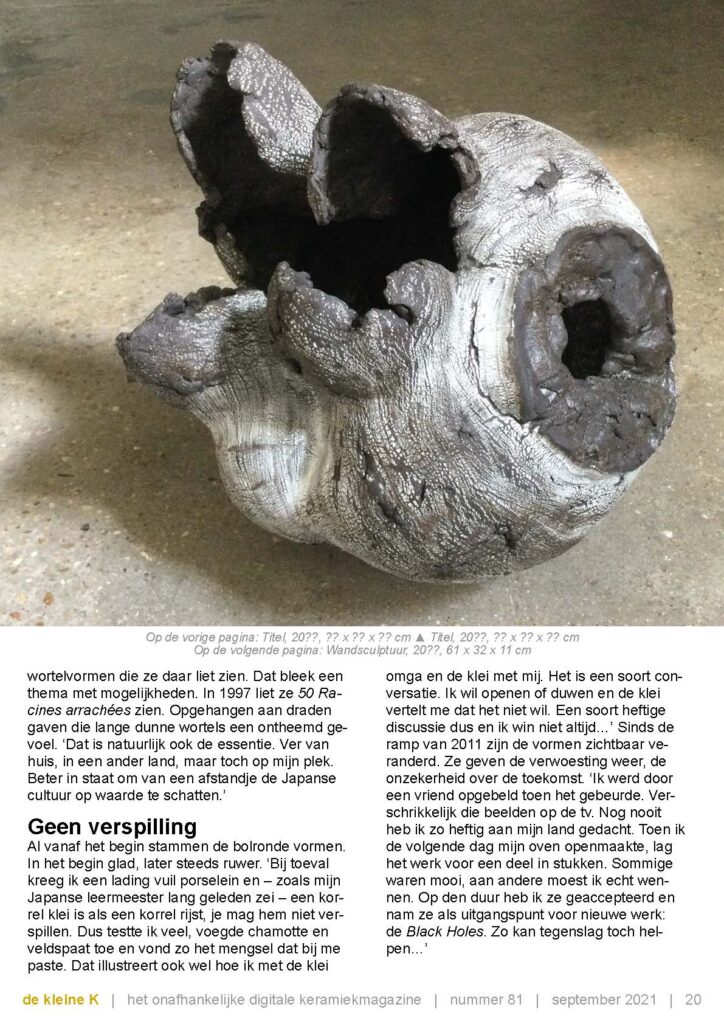

Yoshimi Futamura’s large objects are intriguing. Their rough, grainy exterior is reminiscent of ancient weathered rock formations. At the same time, round shapes are very organic, they seem born and grown. They show Japan’s connection with nature.

For Yoshimi Futamura (Japan, 1959), nature is the most important source of inspiration. “For the Japanese, it’s very obvious. The nature that surrounds us is grandiose and at the same time threatening: the beauty of the sakura, the cherry blossoms, against the horror of the tsunami. As a people, we have learned to live with it and have developed a deep respect for it. This is also reflected in the most important religion, Shintoism. Animism gives everything around us a divine essence. I want to represent this feeling of connection and respect in my pieces. »

The large objects that Futamura is known for also evoke this feeling of respect. They are crude on the outside and contain something mysterious.

Yoshimi grew up in a village near Nagoya, on Japan’s largest island, Honshü, and near the important ceramic towns of Seto and Tokoname. “We were a traditional Japanese family and we lived in the middle of the rice fields, an hour’s walk from the school. There was always tea: not just when I came home or when there were visitors, but all day. I was quite a curious child and I remember sneaking up to the cupboard where the tea bowls were kept just to touch them. This was my first contact with ceramics. Later, when I was already in high school, I saw a documentary about Shoji Hamada on television. They showed him working in his workshop. This enchanted me and I immediately thought that we could make a career out of it, which is what I want too! My family was less enthusiastic, but I still went to study ceramics in Seto, an hour’s round trip each day.

At that time, there was a complete revival of (ceramic) craftsmanship and the Seto school was very popular, even among foreigners. I stayed there for three years, then I went to work in a factory where traditional ceramics were made. She stayed there for seven years, during which she deepened her knowledge of Japanese crafts by visiting numerous exhibitions.

Around 1986, Yoshimi Futamura thought it was time to find his own way. She took a year off and went with a friendship organization to Sri Lanka. The world opened up to me and I realized I could be anywhere in the world. This became evident when I went to Paris. I didn’t speak the language, but I was able to adapt quickly. I was the first Japanese to study at the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré (1989-1994).

Students came from all over the world and I felt at home. Japanese art and culture were very popular in Paris at the time, with many exhibitions on crafts.

It was time to create my own work and release it to the world. Yoshimi has received offers to exhibit in galleries in Paris. There was virtually no ceramics market like that of Japan. From the start, nature proved to be his inspiration: the exhibitions were entitled Vagues de terre and Sous la terre (underground). The latter referred to the first

shapes of roots that she showed there. This turned out to be a theme full of possibilities. In 1997, she exhibited 50 Roots snatched. Suspended by threads, these long thin roots gave the impression of movement. “That is of course also the main thing. Far from home, in another country, but still at home. Better able to appreciate Japanese culture from a distance.

Convex shapes go back to the beginning. Smooth at first, then becoming more streaked. “By chance, I received a load of dirty porcelain and – as my Japanese teacher said a long time ago – a grain of clay is like a grain of rice, you shouldn’t waste it. So I tested a lot, added chamotte and feldspar and found the mixture that suited me. This also illustrates how I work with clay. It’s a kind of conversation. I want to open or push and the clay tells me that it doesn’t want to. So it’s kind of a lively discussion and I don’t always win…” The shapes have visibly changed since the disaster of 2011. They reflect the devastation, the uncertainty about the future. “A friend called me when it happened. These images on television are terrible. Never before had I thought so intensely about my country. When I opened my oven the next day, some of the work was in pieces. Some were beautiful, others really took some getting used to. Finally, I accepted them and took them as a starting point for a new work: Black Holes. This is how adversity can still help…’